Over the past decade the prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has increased to the extent that it is now endemic in many countries around the world. The European SENTRY study of 2001 established that the incidence of MRSA varied, not only from country to country but also within countries. For example, the highest prevalence rates (43%) in Europe are in Portugal and Italy and the lowest are in Switzerland and the Netherlands (2%). Increased prevalence rates are not confined to Europe, but have also been identified in Brazil, Slovenia and Canada.

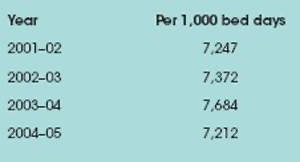

In the last decade in the UK the incidence of infections caused by MRSA has dramatically increased, to the extent that MRSA is estimated to cost the National Health Service (NHS) £1bn a year. In recognition of the problem, the Department of Health (DoH) introduced several campaigns from 2001–04 to combat MRSA, and in 2004 the health secretary set targets for a 50% reduction in MRSA by 2008. Mandatory surveillance figures (England only) released by the Agency for Communicable Diseases (Table 1) suggest that MRSA is still a headache that will not go away.

MRSA ACQUISITION AND COSTS

MRSA acquisition is a particular problem among critically ill patients, and intensive care units have the highest incidence of MRSA. The acquisition of MRSA can be attributed to the overuse of multiple antibiotic therapy. Initially it was viewed as a hospital-acquired infection.

However, MRSA is now more prevalent in the community, which means that an increasing number of patients are being admitted to hospital with MRSA colonisation or infection. The National Audit Office estimates that nosocomial infection prolongs hospital stays by, on average, 11 days, at a total cost some 2.8 times higher than the cost of hospitalising uninfected patients.

The burden of disease attributable to MRSA infection is immense in terms of morbidity and mortality, increased duration of hospitalisation and resource consumption. Even before infection has set in, colonised patients require increased healthcare resources, as numerous measures must be taken to limit the spread of MRSA to other patients. Investigators in Canada, using a cost model, have estimated that the additional cost per patient episode arising from MRSA colonisation (without infection) is equivalent to £650.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataMRSA PREVENTION AND CONTROL

The prevalence of MRSA is not uniform globally, and many countries have virtually eradicated it from their healthcare setting or have it under control. The implementation of isolation, contact precaution, decolonisation therapy, hand hygiene and admission screening strategies are recommended ways of improving infection control measures and preventing avoidable infections, but there is still a lack of evidence for the efficacy of these interventions.

ISOLATION AND DECOLONISATION

Current guidelines recommend that isolation, contact precautions and decolonisation are important in the control of MRSA. However, a systematic review by Cooper and colleagues found no evidence to support the use of isolation measures. Furthermore, a prospective study found no increase in the prevalence of MRSA when patients were not isolated.

Although universal precautions and good hand hygiene are the standard requirements when caring for a patient, additional contact precautions are advised when patients have MRSA. Contact precautions require cohort nursing or nursing the patient in isolation, and equipment must not be shared with other patients. Extra precautions at the bedside are needed: the nurse must wear gloves and a gown constantly when in conta ct with the patient. However, the constant wearing of gloves has been identified as a source of microorganism transmission. They can discourage hand washing, inadvertently leading to an increase in transmission.

Colonisation is an identified risk factor for acquiring MRSA. Nasal colonisation accounts for up to 35% of all clinical isolates in European and US Hospitals. Several studies have shown that the successful elimination of nasal carriage has reduced MRSA infection rates Current decolonisation therapy consists of mupirocin nasal ointment and a chlorhexidine or triclosan body wash.

However, decolonisation is not always successful and there is a high risk of inducing resistance. It is unclear if this is a cost-effective long-term intervention. Interventions to control MRSA can only be implemented after MRSA is detected, while sub-optimal detection methods delay the implementation of these interventions. This emphasises the importance of finding a more rapid method of detecting MRSA.

HAND HYGIENE

The hands of healthcare workers have been identified as a source of transmission for micro-organisms, and it is generally acknowledged that hand washing is the most important and effective intervention to prevent MRSA infection. It is also simple and cost effective.

Yet despite this, poor compliance with hand washing guidelines is well documented. Interventions aimed at increasing hand hygiene, such as audit and feedback, education and training, posters to remind healthcare workers to wash their hands and the introduction of alcohol hand rubs have had mixed success.

The barriers to compliance have been identified as a lack of time and facilities, and skin irritations. Although the introduction of alcohol hand rubs has led to improved compliance, they are only designed to be used at the bedside if hands are not soiled, as they are ineffective as a cleaning agent.

A decrease in the incidence of MRSA bacteraemia and nosocomial colonisation after introducing alcohol gel rubs has been demonstrated, but such success has not been replicated worldwide. Although the implementation of alcohol rubs may help to some extent, it fails to address wider social and behavioural issues and therefore must not be viewed as a quick solution to the problem of MRSA.

SCREENING PROGRAMMES

It appears that, although many patients begin by being colonised without any clinically evident infection, 30–60% of colonised critically ill patients subsequently develop an infection syndrome attributable to the organism. In fact, colonisation pressure is a major independent predictor of MRSA infection in a given critically ill population.

Reducing the prevalence of MRSA among hospitalised patients requires prompt identification of colonised individuals. The current screening technique using a standard culture base takes more than 48 hours, during which time non-colonised patients may be at risk of MRSA acquisition arising from exposure to colonised patients. This risk may also apply to healthcare workers who have prolonged contact with colonised patients. A quicker method of detection is therefore essential.

A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test is a more rapid way of detecting for MRSA, providing results on the same day. There are many different types of PCR tests available, but they are still in their infancy and are expensive. Also, further confirmation is required of the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of PCR diagnostic techniques to allow the rapid detection and improved control of MRSA transmission.

COLONISATION PREVENTION

So would it not be better to prevent colonisation? Tea tree oil (TTO) is a naturally occurring chemical with broad microbicidal activity that is known to act upon MRSA. Only a small number of clinical trials have been conducted using preparations containing TTO. These have established that topical formulations can eradicate MRSA skin colonisation.

In a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of TTO (4% nasal ointment and 5% body wash) compared to routine care (nasal mupirocin and triclosan body wash) for MRSA decolonisation, five out of 15 patients in the TTO group compared with two in 15 in the routine care group were successfully decolonised, although this difference was not significant, due to the small sample size.

In the second published RCT for MRSA decolonisation, 224 patients were enrolled and received either standard treatment (nasal mupirocin and chlorhexidine body wash) or TTO (10% nasal cream and 5% body wash). Overall, 41% of those receiving TTO were successfully decolonised, a figure comparable to the success rate for standard care.

In spite of the laboratory and clinical evidence supporting the efficacy of TTO in eradicating MRSA, there are no published data evaluating its role in preventing MRSA acquisition. Since TTO is effective and has low toxicity, and its use as a prophylactic would not encourage MRSA resistance to a current treatment – as it is not part of the standard therapeutic armoury – this would be a logical line of enquiry.

A large RCT is currently being undertaken to investigate the efficacy of 5% TTO body wash in preventing colonisation of MRSA in ICUs. If successful, this intervention would be easy to implement in any healthcare setting. Prevention of colonisation can make a huge impact on MRSA infection rates and bring us one step closer to reducing the prevalence of MRSA.

COLLECTIVE EFFORT

Although individually some MRSA prevention strategies lack credibility, collectively they appear to have an impact on infection rates in certain countries, so it is important that current guidelines continue to be adhered to and enforced until further evidence or new therapies are found.

Current interventions, such as contact precautions, isolation and decolonisation therapy, are hampered by suboptimal methods of detecting MRSA, and it is imperative that a method of early detection is found.

Hand hygiene is still recognised as one of the most important infection control measures to prevent transmission of infection to other patients. However, hand hygiene compliance is often poor. The introduction of alcohol gels must be viewed with caution, as it may only temporarily mask a problem that has been ongoing for decades.

Further research should focus on prevention and early detection of MRSA, the social, behavioural and organisational factors that influence its spread, rapid screening methods for the early detection of MRSA and alternative therapies such as TTO.